FINNISH DISABILITY FORUM 2023

Download Word file

presented to the CRPD Committee pre-sessional working group for the 18th session as a submission by Finnish Disability Forum (Finnish OPD) for the list of issues in relation to the initial report of Finland

Introduction

Finnish Disability Forum

The Finnish Disability Forum is a co-operative organization of 27 national disability organizations established in 1999 to promote the social status and well-being of persons with disabilities. Finnish Disability Forum represents Finnish disability organizations in national and international cooperation, especially in the European Disability Forum (EDF). The Finnish Disability Forum’s domestic advocacy activities focus on ensuring equal participation of persons with disabilities.

The results presented in the report are based on a survey conducted jointly by Finnish disability organizations and the Human Rights Centre. Its results are referred to in the text as the VF survey (VFS). The survey was conducted in spring 2018, just under two years after the ratification date, and highlights the perspective of persons with disabilities on how the entry into force of the CRPD has influenced their lives. The survey responses provide a unique, valuable, and comprehensive picture of the challenges experienced by persons with disabilities in Finland today.

The questions were based on the rights and objectives of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The online questionnaire was available in Finnish and Swedish from 27 March to 30 May 2018. In addition to the online questionnaire, there was also a PDF-based printable version of the questionnaire to improve accessibility. A cover letter was also sent with the questionnaire, explaining in more detail the purpose of the responses and the significance of the initial state report.

The opportunity to respond to the survey was advertised through, for example, the Finnish Disability Forum’s own and member organizations’ networks. In practice, the survey was made visible on the website, in social media and in personal encounters, for example at various events. Despite the large number of respondents (more than 2000), a significant number of responses (around 25%) were not completed. The non-responses are not discussed in this report.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

There are serious problems in the implementation of the rights of persons with disabilities in Finland, notwithstanding that the legislation and the system of services are appropriate on the surface, problems in the implementation affect to such an extent as to significantly threaten the realisation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons with disabilities; the most important ones we want to raise are the following:

Failure to comply with the obligation to ensure full participation and inclusion, together with only apparent inclusion prevent and delay the realisation of the rights of persons with disabilities. Inclusion is also lacking at the level of client processes in disability services.

One of the main causes for problems in the fulfilment of rights of persons with disabilities is the competitive tendering of disability services, which emphasises low prices at the expense of quality. As a method of organising services, competitive tendering infringes on the participation of persons with disabilities in matters that concern them, since only the commissioner and the provider of the services are recognised to have legal standing in these cases, not the client with disabilities themselves.

Finland has not taken enough measures to stabilise and secure the status and funding of organizations of persons with disabilities (OPD), including the national umbrella organisation, Finnish Disability Forum. Rather, the funding of organizations is in constant decline, and the reorientation of funding severely threatens their functioning and autonomy, and thus full inclusion and participation of persons with disabilities.

The inclusion of children with disabilities and their right to express their views and to be heard on matters that concern them is not realised especially for children with hearing and speech impairments. Children with disabilities are significantly more likely than other age groups to go without personal assistance, although the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has repeatedly drawn Finland’s attention to this (CRC/C/FIN/CO/4, para 40 b). Children with disabilities even end up in child protection services or placed outside the home because the services their families need are not available. Inclusion in the education system has been implemented without the necessary disability support being provided in the child’s local school. There are also accessibility deficiencies in educational institutions.

Accessibility issues in Finland concern as well the built environment and digitalisation as services. Accessibility is not sufficiently recognised in legislation. The construction of accessible housing continues inadequate and public transport is not accessible to all, even in the largest cities. Educational facilities are deficient in accessibility. Many online services are not accessible for all. Cognitive accessibility is often overlooked. Digitalisation improves accessibility of services for some persons with disabilities but excludes some people with visual impairments and people with cognitive disabilities from the activities of society.

The exceptional circumstances caused by the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated many of the challenges to the implementation of services and rights for persons with disabilities. For example, services were terminated without any decision being taken to terminate or replace the service. The right of persons with disabilities to see their relatives or necessary professionals was unlawfully restricted in residential services.

The right of persons with disabilities to exercise their legal capacity is insufficiently implemented in Finland, especially for persons who need support to do so. The exercise of legal capacity is increasingly dependent on having strong electronic identification tools, mainly bank credentials. These are very difficult to obtain if a person needs the assistance of another to use them, because of a physical or cognitive disability. Such reasonable accommodation is allowed in this case, yet rarely offered.

Legal certainty for persons with disabilities is not sufficiently implemented in Finland.

There is no regular assessment of the impact of legislation on persons with disabilities, nor is there a systematic assessment of the impact of legislation on persons with disabilities at the level of its implementation. Even the highest courts are not sufficiently familiar with or do not apply the UN CRPD. At the level of public officials, the CRPD is often completely left aside. Public authorities draw up and follow implementing guidelines which are often contrary to the law and case law, leading to non-grounded and lengthy appeal procedures. There are no sanctions for the use of unlawful implementing measures. Both the supervision of services and its resources are inadequate; and self-monitoring, which is a key element in monitoring, is not effective, as evidenced by the many legality review decisions. Attempts to address the deficiencies may lead to retaliatory measures against the client or the relatives.

The right to self-determination of persons with disabilities is being restricted in services in ways that are not in accordance with the law. Violence against persons with disabilities, especially women, is more common and more serious in Finland than violence experienced by non-disabled persons. Children with disabilities also experience more emotional and physical violence than their non-disabled peers.

There are not enough housing options to meet the individual needs of persons with disabilities and, for the most severely disabled persons, the choice of housing is mainly in the form of group accommodation, where the right to self-determination is poorly exercised (Article 19, cf. CRPD/C/GC/5, para. 24). The implementation of personal assistance and transportation services also faces challenges. There are varying interpretations of the conditions for granting personal assistance by public officials and courts, and serious problems with the availability, turnover and skills of assistants. Lack of support for independent mobility and transport jeopardises the inclusion of persons with disabilities in many areas of life.

Within the services system, discretion is not being applied in individual cases, which has led to the emergence of groups-in-between. For example, persons who are neurodiverse, with rare diseases, brain injuries or mental ill health are often excluded from the sphere of both disability services and the general social services; this exclusion can lead to an escalation of problems and the need for more burdensome services later.

More often than the rest of the population, persons with disabilities must live their whole life course depending on minimum social security, as disability-related extra costs are not fully covered. Life with a disability is too often a life in poverty, as even a good education does not significantly increase either the rate of employment or income of persons with disabilities. Employment discrimination against persons with disabilities is common, but it remains largely invincible to the judiciary, which makes it even more difficult to solve.

Finland has not taken sufficient action to produce systematic data on issues concerning the rights of persons with disabilities, which makes it difficult to solve any of the problems.

On 1 March 2023, Finland adopted a reform of its disability legislation, which alone will not be enough to remedy the problems described above, especially as the funding of the new legislation is a major concern. The entry into force has been delayed till October 2024, a new Bill will be drafted.

The inclusion of disability organizations is essential to ensure that the voice of persons with disabilities and the specific expertise the OPDs have about the daily lives and problems faced with disabilities, as well as on the application of legislation and the lack of implementation of services, all these are made available to the authorities developing legislation and services. The current lack of inclusion leads to a lack of respect for the fundamental and human rights of persons with disabilities and even to serious violations of their human rights.

Part 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS (Articles 1-4)

Finland has not succeeded in implementing the information and protection obligations of the Convention. The Parliamentary Ombudsman and the European Court of Human Rights have pointed out to Finland’s problems of monitoring the implementation of the legislation and the realization of legal protection which have not been solved by the State and which are also set aside in the initial report.

A particular challenge in applying the existing laws is that there is no general definition of disability in Finland, but each substantive law has their own definitions in relation to each service or support measure. The Convention’s definition of disability has not taken root and a medicalized definition of disability still prevails.

In 2015, when adopting amendments to the Act on Special Care for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (Act on Persons with Intellectual Disabilities), Parliament required the Government to continue to develop the regulation of self-determination (initial report, para 9). This legislative work is still ongoing. The amendments to the legislation on Non-discrimination (initial report, para 10) are also insufficient even after the 2015 and 2022 reforms: for example, failure to provide adequate basic level of accessibility is not included as a form of discrimination in the definition.

The 2018–2019 Action Plan to promote the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Initial report, para 15) was implemented only partially. The measures in the Action Plan, which is drawn up by the Advisory Board on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (VANE) in cooperation with the ministries during each government term, have remained general in nature, with limited State commitment and practical implementation. Interdepartmental co-operation has not been achieved.

Reform of disability services legislation (initial report, para 21) has been delayed many times. The new Disability Services Act was finally adopted on 1 March 2023, but its actual implementation is threatened by the severe under-budgeting of disability services, starting already in 2016 in the over 300 municipalities. The under-budgeting seems to be continuing in the 21 welfare service counties and the city of Helsinki, larger regional units to take over from the municipalities the organizing of social and health care, emergency services in 2023.

Consultation, inclusion, and participation of OPDs (initial report, paragraph 25) is still partly random, varies from one administrative sector to another, and is mainly carried out on disability-specific issues. A systematic disability impact assessment was only be included in the Impact Assessment Guidelines for the preparation of legislation in 2022[1]. It remains to be seen whether this will improve the involvement of persons with disabilities and their representative organizations in the preparation of legislation concerning them.

Municipal disability councils (Initial report, paragraph 26) have varying levels of operational resources and effective access to influence. This seems to be the case for disability councils in welfare service counties. A new risk has been identified, namely that attempts are being made to limit the direct involvement or inclusion of OPDs based on the existence of disability councils.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- complete the national legislation to strengthen the right to self-determination?

- include the failure to provide accessibility in the Non-discrimination Act as a prohibited form of discrimination?

- increase the knowledge and skills of public authorities and legal professionals about the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities?

- improve disability policy objectives and implement measures across government periods?

- systematically carry out disability impact assessments as part of the preparation and monitoring of legislation?

- achieve more systematic, sustained, and effective inclusion and full participation of persons with disabilities and OPDs?

- monitor and evaluate the implementation of the new Disability Services Act and, if necessary, revised in cooperation with OPDs?

- monitor and evaluate the impact on persons with disabilities of the reform of the social welfare system and the transfer of responsibility for the organization of services to the welfare service counties and any shortcomings addressed?

PART II SPECIFIC PROVISIONS (Articles 5, 8-30)

Article 5 Equality and equal treatment

There is discrimination and a reluctance to improve the inclusion of persons with disabilities in Finnish society. More than 50% of respondents to the VFS felt that attitudes were poor, and 64% had experienced discrimination in some area of life.

Discrimination and discrimination at work are criminalized in the Criminal Code, and disability is a prohibited ground of discrimination in the Non-discrimination Act. Discrimination on the grounds of disability is commonplace, but these cases very seldom are taken to, or acted upon by the police or by the courts. According to a survey conducted by disability organizations, between 2016 and 2019, 59 cases of either employment discrimination or discrimination were heard by district courts, of these 59 only two were based on disability. During the same period, in decisions not to prosecute or to limit preliminary investigations, disability as a ground for discrimination appeared more frequently. In 54 decisions not to prosecute in cases of suspected discrimination and employment discrimination offences, 11 of the 54 decisions not to prosecute and 69 decisions to limit preliminary investigations included disability as a ground for discrimination. The initial report does not deal at all with discrimination from the perspective of criminal law and legal protection.

The obligation to make reasonable accommodations applies only to public authorities, education and training providers, employers and providers of goods and services under the Non-discrimination Act. For example, housing associations, associations and political parties are excluded from the scope of the Act. Very few – less than 2% – employers are covered by the equality plan mentioned in the initial report (for those employing minimum 30 people), as 98.3% of companies employ 20 or fewer people, according to Statistics Finland. Persons with disabilities continue to face discrimination both in leisure and in workplaces; one in three say they have experienced discrimination in the last five years at work or when looking for a job[2].

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- the provision on reasonable accommodation in the Non-discrimination Act is extended to be compliant with the CRPD?

- promote the use of positive discrimination, reasonable accommodation, and other measures to promote non-discrimination, including sanctions?

- monitor the implementation of equality plans?

Article 8 Awareness raising

A third of respondents to the VFS felt that prejudice against persons with disabilities had increased and almost half felt that respect for persons with disabilities had decreased in the first years of the application of the Convention. 46% of respondents had experienced inhuman treatment and 69% had experienced degrading treatment. The entry into force of the Convention does not seem to have improved the situation of persons with disabilities.

The Non-Discrimination Ombudsman has also reported on the prevalence of inappropriate behavior, prejudice, and discrimination against persons with disabilities, which she sees as a reflection of negative attitudes and a lack of information and understanding[3] : “we treat persons with disabilities as if they were second-class citizens somewhere outside our everyday lives.”

Inadequate awareness-raising efforts and resources (paragraphs 45-50 of the initial report) make it difficult to implement the measures required by the Convention. There is a lack of awareness of the CRPD among ministries and other public administrations, and the initial report does not propose concrete measures to improve this awareness or the position of persons with disabilities in society. This work is left largely to the organizations, nevertheless Finnish Disability Forum receives no public funding for its work, apart from dedicated funding to Hilma – The Support Centre for Immigrant Persons with Disabilities and long-term Illnesses.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- provide more widespread and systematic information on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities at different levels of society?

- raising awareness of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities among social and health services, early childhood education and training?

- secure adequate resources for DPOs and the Finnish Disability Forum to be able to fulfill their role in CRPD implementation in accordance with CRPD 4 (3) and 33 (3)?

Article 9 Accessibility

Built environment

Up-to-date research data on accessibility of buildings is needed. The last survey on accessibility of residential buildings and courtyards was carried out in 2012[4] , and only 15% of the housing stock is accessible.

Of the respondents to the VFS, 40% had encountered accessibility problems quite often or constantly (Table 1). The responses reflected the negative attitude of different stakeholders towards accessibility. In indoor public spaces, accessibility problems are often related to building entrances (level differences, missing or non-functional ramps), doors that are difficult to open and the dimensioning of lifts. In public outdoor areas, the impossibility of access during snowy periods was highlighted by the lack of winter maintenance.

The Government Decree on Accessibility of Buildings (2017) came into force in 2018, applies to buildings and outdoor areas within their grounds, but not to the majority of outdoor public spaces. The regulation specifically addresses accessibility from the perspective of people with reduced mobility, but not, for example, accessibility of the sensory environment. The Decree does not provide sufficient guidance for the promotion of accessibility in the built environment. Also, the general provision regarding consideration of accessibility in the Land Use and Building Act, or the ministerial guidelines on accessibility are not sufficient to ensure accessibility outside the scope of the Decree. Responsibility for accessibility is spread across too many actors to sufficiently realize it in practice.

Public transport

The initial report (paragraph 64) refers to EU regulation on accessibility of public transport, but these regulations are focused on rights of passengers with reduced mobility, and as such do not guarantee accessible public transport. Public transport equipment and stops are largely inaccessible. Access to transport usually requires the assistance of another person and independent mobility is not possible. Drivers do not always provide assistance to disabled passengers to access the vehicle. Even in large cities, there has not been sufficient upgrading of bus stops, nor has there been sufficient provision of accessible transport for long-distance travel[5].

The reform of taxi regulation (initial report paragraphs 65-69), especially market deregulation, caused severe disruption: shortcomings in distribution, safe vehicles, and driver skills. While it has been largely withdrawn, and legislation reintroduced, problems persist in subsidised, adapted, and accessible transport services. Continuing rounds of competitive tendering for transport is pushing down service prices. This has reached the point where access to the service for clients who rely on the service is increasingly compromised, particularly in rural areas. Journeys are being made excessively longer by obligatory pooling: This means that a 20-minute journey can take up to 1.5 hours due to combinations[6] of travel, making use of the service increasingly difficult.

Services

Persons with disabilities also need social welfare services other than disability services. However, the accessibility of services and the reasonable adjustments needed to facilitate their use are not ensured, even though, for example, research evidence shows that substance abuse services have a higher proportion of disabled clients than their share of the population[7].

Schools and workplaces

37% of respondents to the VFS had experienced problems with accessibility or accessibility in the workplace and 45% in educational institutions. Attitudes were reflected in a lack of understanding of disability and misunderstandings in communication situations.

Accessibility challenges in workplaces and educational establishments include entrances, the absence or small size of lifts, the absence of induction loops and guide rails in passageways, the inaccessibility of toilets and the cramped working spaces for people using assistive devices. There are problems with information and social accessibility, such as support for interaction and communication.

Employers are not aware of the construction of an accessible environment and the support available for changes in working conditions. Disabled workers do not always know what kind of work support they would be entitled to.[8]

Accessibility of ICT

The initial report (paragraph 81) describes the assessment of website accessibility. Website operators can use the form published by the Regional State Administrative Agencies to report on the accessibility of their website[9], and website users can report accessibility problems. However, the State does not carry out accessibility monitoring on a sufficiently large scale. The VFS (Table 2) identified problems with public services, with call-back systems. Many services are only available by telephone, which discriminates against people with hearing and speech impairments. Even the initial report (paragraph 79) states that all information should be available in both voice and text.

To access many essential services, strong electronic identification tools such as online banking credentials are needed, but these are not given to a disabled person in need of assistance to use the credentials. This is justified by the legal requirement to personalize the tokens. The 2017 amendment to the Credit Institutions Act was intended to facilitate access to online banking IDs for persons with disabilities. According to the explanatory memorandum of the Government Bill, banks must accept the use of an assistant for basic banking services, such as bank IDs, as a reasonable accommodation.[10] Yet it is very difficult for people with intellectual disabilities, for example to obtain online banking IDs. The Initial report completely ignores addressing the problem of unequal access to strong electronic identification tools (Article 12).

In addition to technical accessibility, cognitive accessibility, such as clarity and comprehensibility of language, must be taken into account. In 2015, only 10% of municipalities had produced materials in easy-to-read language (Initial report, paragraphs 280-281), even though there are around 750 000 people in Finland who benefit from easy-to-read language[11]. Ensuring accessibility of services is essential to prevent persons with disabilities from being excluded. However, access to digital services is either not sufficiently accessible or relies on the help of people close to them.

The introduction of the emergency text messaging service introduced in December 2017 in the emergency services requires strong authentication and periodic renewal of registration (Initial report, paragraph 98). SMS messages from an unregistered number will not reach the emergency call centre, which in the worst case could lead to the death of the person in need of help. The obligation to register is not due to be lifted until 2025. Contrary to the Initial report, the sign language emergency call pilot only started in June 2021[12] and will end in 2023. The service will only be open during office hours.

In Finland, even the major actors are not yet familiar with the principle of design for all. For example, the capital’s public transport ticket vending machine reform was carried out in the knowledge that it was unsuitable for persons with visual impairment. After the Equality and Non-discrimination Tribunal of Finland found the reform to be discriminatory, all visually impaired people were granted the right to free travel. A common electronic study system for the big four universities is not accessible for students with visual impairment. Accessibility testing was not carried out and it will take years to make the system accessible afterwards[13].

Proposed questions

What action will the Government take to:

- clarify the current state and gaps in accessibility regulation from a fundamental and human rights perspective and improve the coherence of regulation?

- ensure that the current state of accessibility of the built environment is assessed and reliable and accessible information on accessibility of facilities is available?

- increase national regulation, use of design for all -principle and bring more clarity to the responsibilities for accessibility?

- new and renovated buildings take greater account of the sensory, visual, and auditory environment?

- mainstream accessibility and equality across all private and public service providers?

- provide better information and training on accessibility and its regulation for building operators?

- repeal the waivers of accessibility regulations for housing and reinstate the duty to stand and be on call that was removed from taxi drivers?

- persons with disabilities are involved from the start in the planning, design and testing of services for accessibility and accessibility?

- promote cognitive accessibility?

- ensure ICT accessibility to emergency services?

Article 10 Right to life

Around 27% of respondents to the VFS had felt their right to life had been directly or indirectly challenged (Table 3), and around 50% for children with disabilities. Many had felt that their right to life on an equal basis with others was being challenged by poor access to services and support, negative attitudes from public authorities and the public debate on euthanasia and Do-not-resuscitate orders.

According to disability organizations, families of children with disabilities are often advised to limit treatment to resuscitation, intensive care, or life-sustaining treatments, for example. Restrictions are proposed and imposed on children with disabilities who are not in hospice care or near death. In residential care units, it may be suggested that a limitation of treatment be imposed, although the treatment guidelines must always be made by a doctor and based on up-to-date medical evidence. The Parliamentary Ombudsman has drawn the attention of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District to a guideline that restricted the right to (intensive) care for disabled children[14] .

In Finland, in practice, parents are advised to have antenatal screening and the risk of abnormalities or injury is presented as a reason to terminate the pregnancy. Sufficient support is not available if a family decides to keep the child despite a confirmed disability or structural abnormality during pregnancy.[15]

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure that disability is not used as a criterion for limiting treatment, and treatment limits do not violate the right to life or health services of persons with disabilities?

- make unbiased information and support available during pregnancy and childbirth in case of suspected disabilities, illnesses, or abnormalities?

Article 11 Emergencies and humanitarian emergencies

In 2020, the Covid19 pandemic caused accessibility problems for persons with disabilities to information, service closures and illegal bans on visits, as well as questions about access to appropriate care. In the early stages of the pandemic, emergency information was not available in accessible and multilingual formats. The Ministry of the Interior has included sign language information in its guidelines for crisis situations (initial report, paragraph 100), but sign language interpretation was only provided for the live televised information sessions of the Council of State after reminders. Initially, subtitling was only available on the Internet, although the legislation has long required television subtitling.

During the pandemic, disability services were discontinued in several municipalities without any decision or any replacement services, due to the pandemic situation. The closure of day and work activities also caused income losses and livelihood problems.[16] The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health had to remind municipalities that services must not be closed completely, even in exceptional circumstances, and that delays in services must not jeopardize everyday life and safety. Access to services must be ensured, especially for the most vulnerable[17].

Visits to residential care units were banned on the grounds of health and safety of residents and staff, including vital physiotherapy, interpretation, and assistance services. Not all persons with disabilities had the equipment or skills to communicate remotely with their loved ones or to use online services. As the general restrictions were relaxed, absolute visiting bans could persist in residential services, and not all residents could even go outdoors. The Parliamentary Ombudsman ruled that categorical bans on visits were illegal[18].

During the first wave of Covid, there was a public debate about whether persons with disabilities would be treated equally if there were a shortage of intensive care places.[19] A complaint was lodged with the Parliamentary Ombudsman against the prior limitation of ventilator treatment for a disabled person[20] in violation of the Convention provision on the dignity of every life. In a pandemic situation, the service system was also unable to meet the service needs of children with disabilities and their families. Even essential services such as rehabilitation were suspended and in some families the education of the disabled child was left to the parents. In autumn 2020, a clear learning deficit was identified in many children[21].

The exceptional circumstances showed that the situation of persons with disabilities requires special consideration. The lack of legislation on self-determination also weakens the position of clients and patients in exceptional circumstances. Despite requests, the Ministry of the Interior has not engaged in cooperation with disability organizations to ensure that persons with disabilities are adequately taken into account in possible disruption, crisis and emergency situations. For example, there is a lack of information on how to evacuate persons with disabilities, how to consider the use of electronic aids in the event of a power cut, and how to ensure that public alarms reach people with hearing impairments. The initial report presents the provisions of the Emergency Preparedness Act, but it does not show how they are implemented and monitored.

Discussions with the authorities shift the responsibility to persons with disabilities themselves and to organizations, which cannot, however, replace the authorities in emergency situations. As a result of the interest rate crisis, there were large-scale redundancies in the largest national social and health organizations[22], even though the need for information and support from organizations had increased even more.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- take into account and ensure the survival of persons with disabilities in times of disruption, crisis, and emergency?

- make crisis information accessible, real-time, and equal for persons with disabilities?

- ensure the continuity of services to maintain the functional capacity and life of persons with disabilities and to ensure equality of treatment in exceptional circumstances?

- ensure that the education of children with disabilities is provided in exceptional circumstances in accordance with individual needs and without placing a burden on their carers?

Article 12 Equality before the law

The Finnish system of guardianship contains elements of decision-making on behalf of others, and the Guardianship Act regulating guardianship is not fully compatible with the obligations of Article 12. The law allows for the declaration of a person with a disability as an incapacitated person (Article 18), and income from property under the trustee’s care is directed only to an account declared by the trustee (Article 31). In practice, this significantly restricts the right of a person with disability to manage his/her/their property, even if the person is not incapacitated.

The rights under Article 12 are also hindered by the difficulty for persons with disabilities to access strong electronic identification tools when they need the assistance of another person to use them (Article 9). Strong electronic identification is required in several situations to exercise legal capacity. Difficulties in accessing identification tools often lead to the need for a person with a disability to seek the assistance of a guardian when there would otherwise be no need.

Supported decision-making

According to the initial report (paragraph 114), the reform of the Disability Services Act and the legislation on self-determination will take into account supported decision-making. No progress has been made in the reform of self-determination legislation for persons with disabilities over several government periods. The new Disability Services Act includes a supported decision-making service, to which a person is entitled if they need support to make important decisions about their own life, other than those that are part of their daily life. The provision states that the disabled person’s own views “shall be taken into account” when assessing the significance of a decision, i.e., the disabled person is not entirely free to determine what is a significant decision for him/her/them. It is uncertain whether the regulation ensures that persons with disabilities can exercise their legal capacity equally in all aspects of life according to their will and wishes and are supported to do so as required by Article 12.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure that the content and application of the Guardianship Act are in no way incompatible with Article 12?

- ensure that the right of a person with a disability to reasonable accommodation, including the use of an assistant, is effectively allowed in use of strong electronic identification and this is raised to the text of the law?

- promote the use of supported decision-making at different levels of society?

Article 13 Access to justice

According to the survey by disability organizations, during the first years when the Convention was in force as national law (2016-2018), 359 disability service cases were decided by the Supreme Administrative Court, of which the Convention was mentioned in only eight decisions or in their reasoning, usually with a brief statement that the decision issued did not conflict with the obligations of the Convention. This suggests that the Convention is still not sufficiently known or applied in courts or by public authorities. In addition, decisions by public officials and appeals procedures often set aside the rights under the CRPD by stating that national law, or even only the municipality’s own implementing guidelines, have been applied. This has also been noted by the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman[23] and the Parliamentary Ombudsman[24] in their reports.

Too often, decisions concerning disability services need to be taken to appeals procedures, which take an unreasonably long time, even years. During this long process, the service is not available to the disabled person. By the end of the appeal process, and after the service has been granted, an old person with a disability or progressive long-term illness often has reduced functional capacity so that the services they have applied for are no longer adequate and appropriate, or they have already died. On the other hand, if a disabled child is deprived of the support the child needs for years because of the appeals process, the child’s development and independence will be severely hampered. Moreover, service providers do not always comply with administrative court decisions[25].

The first stage of the appeal process is to lodge a complaint against the decision of the official. Often, the official who has taken a negative decision or who has instructed the official to take a negative decision also prepares and presents a draft decision to the body responsible for the appeal. In this case, an independent and fair hearing is not ensured, and most appeals are rejected. From 2023 onwards, due to a legal flaw, it is possible that complaints will not even be dealt with by a separate body, but by an official, which will further jeopardize the legal protection of the customer. Many persons with disabilities do not have the time or the skills to draft a complaint or the necessary replies to the complaints procedure. Another problem for legal protection at the appeal stage is that, although legal advice may be available from the legal aid office, the actual legal adviser is not to appear as an agent until the appeal is taken to the administrative court.

According to a report by disability organizations, 6166 social and health care complaints were heard by administrative courts in 2017. Before 2020, it was possible to appeal directly to the Supreme Administrative Court (KHO) against administrative court decisions on disability services guaranteed as a subjective right, but since 1 January 2020, appeals have only been possible if the KHO grants permission to appeal. Appeals are granted extremely rarely: in 2021, 134 applications for appeals concerning disability services were filed, four appeals were granted. In most cases, therefore, the administrative court is the only court hearing and deciding the case.

Legislation requires continuity of services in cases of permanent or long-term support needs. However, people with permanent disabilities or persons with disabilities from birth are often subject to time-limited decisions on service, which undermine legal certainty and unnecessarily drain resources from persons with disabilities, their organizations and the authorities that repeatedly process applications.

Staff shortages, staff turnover and skills shortages delay service decisions and lead to incorrect decisions, jeopardizing clients’ legal protection and access to services. The Parliamentary Ombudsman has repeatedly warned public authorities about exceeding deadlines for assessing service needs and delays in service decisions.

Municipalities are using their own internal guidelines to restrict customers’ legal rights to services[26]. The service provider determines the details of the purchase or implementation of the service, and the services do not respond to individual needs. Individualized provision is particularly compromised when a person with a disability is unable to express his/her/their own needs due to cognitive, communication or social interaction challenges and does not receive the support the person needs to communicate.

Public authorities are failing in their legal duty to provide advice, and customers are not always adequately informed about services, in their own language or using their means of communication. As a result, customers may often fail to apply for a service to which they are entitled. Services guaranteed as a subjective right under the Disability Services Act are also provided to clients based on general legislation, contrary to the rights and interests of the client (client charges, discretionary award)[27].

Disability organizations fill gaps in services by providing legal advice and assistance with appeals processes. However, not all organizations can provide this service due to limited operational funding and many organizations do not have a nationwide service.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure that the duration of the appeal process is significantly reduced?

- ensure that service providers comply with and implement administrative court decisions?

- abolish the obligation to first acquire leave to appeal against administrative court decisions on disability services, which are protected as subjective rights, and speeding up the processing of appeals on other disability services?

- extend the possibility to lodge a complaint or appeal to situations where the authority delays in taking a decision?

- compensate the person with disabilities for delays in the administrative procedure in the same way as for delays in the administrative process?

- ensure that disability services legislation is interpreted in a fundamental rights-friendly way and service providers do not set aside the legislation with their own application guidelines?

Article 14 Freedom and security of the person

Since the ratification of the CRPD, there has been no systematic assessment of the compatibility with Article 14 CRPD of the provisions on restrictive measures in the Act on Persons with Intellectual Disabilities and its application, although this would be justified in the light of the anomalies identified by the monitoring authority. According to reports by the authority responsible for monitoring the strengthening of the right to self-determination and the use of restrictive measures in residential and institutional special care services (Valvira)[28] , the use of restrictive measures has increased, particularly in private services. Scarce human resources and lack of staff skills may also increase the use of restraint measures. In Finland, the construction of housing units with at least 15 clients is favored, although the large size of the unit seems to increase the use of restraint measures.

According to Valvira, decisions on restraint measures are taken by persons who are not competent to do so, and legal written decisions are neglected. Restrictive measures against a person’s liberty are sometimes used more than the time limits set for them, and there are also restrictive measures that are completely unlawful[29] .

According to the Act on Persons with Intellectual Disabilities, the use of restraint measures is conditional on the social welfare service unit having sufficient medical, psychological, and social work expertise to provide and monitor the necessary care and support (paragraphs 133, 134 of the initial report). In 2019, a quarter of the units did not have a specialist team[30] , as required by law, although the law requires the specialist team to know the unit and its residents.

Children are subject to the same provisions as the adults, and the law also allows for severe restrictive measures to be taken against children under the conditions laid down, which is very problematic for the realization of the rights of the child.

The provisions on restraint measures are intended to remain in force only temporarily until the new social and health care self-determination legislation is enacted. It has been set aside over several government periods. Preparations are ongoing; so far there has been little involvement of disability organizations representing different groups of persons with disabilities. There is uncertainty among organizations about the direction in which the legislation is being developed and whether the scope of restrictive measures is being extended to the detriment of the rights of persons with disabilities.

The Parliamentary Ombudsman has drawn attention to accessibility and equal opportunities for disabled prisoners to participate in the prison system during his inspections (initial report, paragraph 148). Inspections have found that the placement of inmates in inmates’ cells has prevented them from participating in activities or has resulted in conditions that are more closed and isolated than required for order and safety.[31] There are areas in prisons that are completely unsuitable for people with mobility aids, and there are no induction loops for people with hearing impairments.[32] Accessibility deficiencies also affect the implementation of proximity meetings if the visitor needs accessibility.

According to the findings of the inspection, a prisoner with reduced mobility or activity may be transferred to a prison hospital if the person cannot cope in the prison environment with the help of prison staff.[33] The assistance and support and reasonable accommodation required for the disability are not adequately provided in prisons. The initial report does not propose measures to address the shortcomings identified in the law enforcement.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- strengthen self-determination, reducing the use of restrictive measures and taking children and young people into account in self-determination legislation?

- end the unlawful use of restrictive measures, against people with intellectual disabilities and people with autism spectrum disorders, in particular?

- provide adequate resources for monitoring services and ensuring the real effectiveness of inspection visits?

- improve accessibility of prisons and equal opportunities for disabled prisoners?

Article 15 Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment

Cases of blatant violations of the human rights of persons with intellectual disabilities and autism, especially children and young people, in the context of services are regularly brought to the public’s attention. Cases of abuse include over-medication, isolation, starvation, restraint, abuse, restriction of movement and restriction of contact with loved ones.[34] Abuse may have gone on for years before being discovered.[35] Psychotropic drugs are prescribed to persons with autism and persons with intellectual disabilities in need of intensive support to control behavioral problems,[36] which is ethically and legally unacceptable and contrary to the current national care guidelines for Autism Spectrum.

The most striking examples of inhuman treatment in the VFS concerned punishments in group homes and unjustified restrictions on movement. Some respondents reported that the staff of the housing unit refused to use speech support and substitution methods, which means total isolation from communication. The open responses in particular report degrading or belittling treatment.

The unlawful use of the restrictive measures provided for in the Act on Persons with Intellectual Disability (discussed in Article 14) may also lead to violations of the rights under Article 15.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- address inhuman and illegal treatment in housing, institutional care, and health care?

Article 16 Freedom from abuse, violence, and ill-treatment

Persons with disabilities are more likely than the general population to experience violence and abuse in their relationships and in the services which they use[37]. Intimate partner violence is most often perpetrated by a current or former spouse or partner, sometimes also by a personal assistant or a social or health care professional.

Between 27% and 43% of persons with disabilities fear being robbed or burglarized, and around 10% often avoid certain streets or areas for fear of violence[38]. Comprehensive statistics on persons with disabilities who have experienced violence are lacking.

More than 15% of respondents to the VFS had experienced physical violence and almost 60% had experienced psychological violence (Table 4). Almost 10% had been victims of sexual violence, abuse, or maltreatment. Almost 25% had experienced other forms of abuse and over 60% had felt unsafe. The open responses to the questionnaire are particularly indicative of experiences of psychological violence and threats of physical violence.

Children and young persons with disabilities experience significant levels of violence, reported as early as four years old (Article 7). Violence against boys and men with disabilities is still not recognized as a separate problem, although they are often subjected to violence, particularly psychological and physical violence, both intimate partner violence and violence perpetrated by strangers. Intellectual disability can also increase men’s risk of experiencing intimate partner violence, and studies show that men also find it difficult to seek and receive help in situations of violence[39].

Disability can make it difficult to seek help. The vulnerability of persons with disabilities is increased by their dependence on the help of another person and their inability to protect themselves from violence, as well as by their invisibility and the minimization of their experiences. Being subjected to physical touch and treatment makes it difficult to recognize the limits of one’s own body and may limit the ability to protect oneself. Up to 28% do not report their experience of violence, only around 50% felt they had received help from the authorities and around 40% felt it was easy to get help. Accessibility and ICT accessibility were perceived as barriers to seeking help, while ignorance, difficulty in the process of seeking help and attitudes were perceived as barriers to receiving help.[40] Violence against persons with disabilities remains hidden and is not sufficiently addressed by professionals. Police do not always take assaults on persons with disabilities seriously but blame the disabled person and interpret disability-related behavioral characteristics as something else, for example, intoxication.

The quality recommendations for shelter services give very little consideration to the specificities of violence against persons with disabilities. Access to shelters remains problematic, as the network of shelters is still sparse, across long distances[41]. Not all shelters are accessible (initial report, paragraph 172) and it may not be possible to contact a shelter except by telephone.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- systematically monitor data on violence against persons with disabilities?

- train professionals in the different sectors on how to identify and intervene in cases of violence?

- combat violence against boys and men with disabilities?

- improve the accessibility of shelters and ensuring accessibility to 24-hour services for people with hearing, hearing-visual, and speech impairments?

Article 17 Protection of the integrity of the person

Almost 30% of respondents to the VFS said their personal integrity had been violated and almost 10% had experienced violations often or quite often (Table 5).

Disability organizations are becoming increasingly aware of cases of social workers pressuring persons with intellectual disabilities and persons with similar support needs to terminate their pregnancy or use contraception, such as subcutaneous contraceptive capsules. The desire of persons with disabilities to have children is also being questioned on the grounds of their disability.

The importance of gender sensitivity for persons with disabilities is not always understood. Women living in housing units have problems with the lack of a same-sex assistant for intimate personal hygiene, despite requests. According to a 2019 ruling by the Deputy Chancellor of Justice[42] , the disabled person’s wishes regarding the gender of the assisting person must be respected and privacy and self-determination must be safeguarded in assisting situations: “[i]t is contrary to fundamental and human rights that disabled persons do not have the possibility to influence who assists them in personal hygiene situations.”

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure that the physical and mental integrity of persons with disabilities is protected in all situations, including as users of services?

- ensure that the privacy and autonomy of persons with disabilities are respected in assistance situations?

- ensure persons with disabilities are not pressured to terminate their pregnancy or use contraception?

Article 18 Freedom of movement and nationality

The freedom to choose where to live (initial report, paragraph 191) is still limited for persons with disabilities by the fact that housing that meets their individual needs is not always available in their municipality of origin.

The support to vulnerable disabled asylum seekers to ensure their rights and obligations in the asylum procedure (initial report, paragraph 151) is not specified in the initial report.

An exception to the language proficiency requirement for receiving Finnish nationality must be made if the applicant is unable to meet the requirement because of his/her/their health condition or sensory or speech impairment (initial report, paragraph 190). However, the derogation criterion is applied more strictly than is required by law; not taking account of the fact that, even if a person does not have a learning disability, the disability may still significantly impede and slow down language learning (for example, practice in social situations).

The cost of applying for citizenship (€460-690 per application) is prohibitive, especially for a disabled person on pension. A person applying for a derogation from the language requirement may have to apply for citizenship and pay the fees several times. Persons with disabilities who are inactive and therefore not in integration training will also have to obtain a language assessment for a fee (€160).

Disability services are not equally available to persons with disabilities who move to the country. For example, the person is only entitled to an interpretation service for persons with disabilities through Social Insurance Institution (Kela) when they have a municipality of residence in Finland and a functional form of communication.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking so:

- persons with disabilities are not forced to relocate involuntarily in the absence of a suitable housing solution?

- the derogation from the nationality language requirement on grounds of health or disability is not interpreted more strictly than the law?

- application and certification costs are not an obstacle to applying for citizenship?

- the services necessary because of the disability will be made available to a disabled person before becoming a resident?

Article 19 Living independently and being included in the community

Housing choices

In the absence of appropriate support services, living with a family is often not possible for persons with disabilities, even for children and young persons with disabilities, who need intensive support.[43] There are difficulties in coordinating housing services with other services (home care, personal assistance), and the provision of service housing in a person’s own home with personal assistance, which is a possibility allowed in the legislation, is not widely used[44].

Funding for housing for persons with disabilities is concentrated on the construction of group homes and housing units, which hinders the development of individual community-based housing solutions[45]. Most persons with disabilities who need help and support with their housing live in residential care units. 42% of the respondents to the VFS had not been able to choose their own housing arrangements. In the Aspa Foundation’s peer review of housing services, 33% of respondents had not been able to choose where they lived, 29% could not choose with whom they lived, and 25% felt that they did not have access to appropriate housing assistance and support.

There are particularly few housing options for people with intellectual disabilities, many of whom must live with their parents as adults (around 5,000 people in 2016). Despite the implementation of the Housing Programme for People with Intellectual Disabilities, institutionalization has been decreasing only slowly: 521 people were in long-term residential care for people with intellectual disabilities in 2018 and 403 in 2021. In particular, the long-term residential placement of children with intellectual disabilities in institutions has not been phased out in line with the targets set by the state (Figure 1).

Municipalities have a great deal of discretion in deciding on home adaptations and the provision and replacement of housing equipment under the Disability Services Act, and the views of the disabled person are often not taken into account in the decision-making process. This even affects the choice of accommodation, and, in the worst cases, the authority’s misjudgments jeopardize the safety of the person with disability in their home (e.g., inadequate smoke detectors, inadequate ramps).

General information on support services for independent living

The organization, accessibility, suitability, quality and functioning of services for independent living also raise many issues relating to legal certainty (Article 13). The lack of resources for services is a structural problem to be solved by administrative and political means.[46] In recent years, staffing levels have been improved in child protection and old people’s services, but not in disability services. The THL survey of municipalities highlights concerns about staffing levels in disability services, both in decision-making and in service delivery, particularly in housing services, but also in personal assistance and mobility services.[47] The cost neutrality sought by the new Disability Services Act does not increase the individualization of services (initial report, paragraph 241).

Responsibility for independent living services or support may also be left to relatives through a nominal family care allowance. This often results in an escalation of problems and ultimately the need for more burdensome services. In addition, for some groups at risk of missing out on disability services (e.g., persons with autism, persons who are neurodivergent, persons with brain injuries, persons with rare diseases) often leads to later use of more burdensome and expensive services (e.g., child protection placements[48], psychiatric institutional care[49]). The service system does not support the coordination of different services and there is no flexible cooperation between officials from different service sectors.

The systemic focus of housing support and institutional traditions[50] perpetuate practices that violate the fundamental and human rights of persons with disabilities. According to the VFS, the institutionalization of housing units limits the autonomy of persons with disabilities and their ability to influence their daily routine, daily life, and leisure activities, and increases the use of restrictive measures (Articles 12, 14 and 15). Similar problems have also been identified in the provision of home health services for ventilator users.[51] Housing inefficiencies and neglect are not mentioned for fear of backlash. The Covid19 pandemic added to the problems described above (Article 11)[52].

The autonomy and self-determination of persons with disabilities is supported mainly when it does not require human resources or conflict with the rules and principles of the service units[53]. Inadequate human resources and lack of staff skills are barriers to self-determination, especially in residential services for people with the “most severe intellectual disabilities”[54], where self-determination would require the support of another person.

Personal assistance

The initial report (paragraphs 216-227) does not sufficiently describe the serious shortcomings in the implementation of personal assistance. 39% of the respondents to the VFS report problems. For example, the granting of personal assistance often sets aside the overall individual situation of the client and the actual need for assistance due to the disability. In practice, even where a service is provided, persons with disabilities do not always receive the assistance they need. For example, the service provider or organizer may severely restrict where, how, and when personal assistance is used, thus failing to meet the requirements of personal assistance in accordance with the criteria set in the general comment on Article 19.

In 2016, 35% of municipalities reported at least some difficulty in organizing personal assistance, that rose to 55% in 2019.[55] The problems include the implementation of the decision, the way the service is organized, the adequacy of the amount of assistance and the complexity of the system. The Parliamentary Ombudsman has called for the adequacy of the value of the personal assistance service voucher to be reviewed when costs rise and, if necessary, in other cases[56] .

The current Disability Services Act makes it a condition for the granting of personal assistance that the person with a disability has the resources to determine the content of the assistance and how it is provided. As noted by the CRPD Committee[57] , this practice has led to discrimination against people with cognitive disabilities because they need support in their decision-making. According to the Committee, control over the service should be exercised through supported decision-making[58], but this is not always allowed in the implementing practice, and therefore the practice has not been fully in line with the CRPD. The new Disability Services Act has slightly relaxed the requirement (the person is capable, independently or with support, of forming and expressing a will as to the content of the assistance) and added a similar new service of special inclusion support for persons who do not qualify for personal assistance.

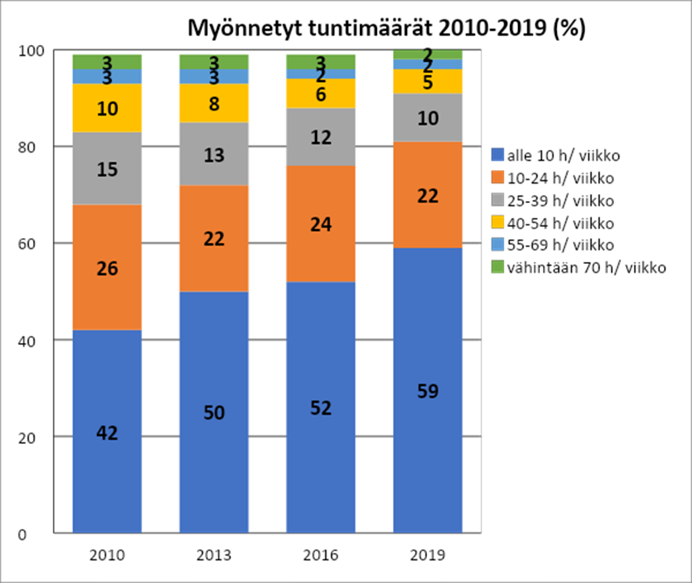

The initial report (paragraphs 222-223) mentions the insufficient number of hours of personal assistance, yet it does not explain the reasons. The assessment of the number of hours is limited to maintaining basic activities of daily living (ADL) and does not take sufficiently into account equal inclusion or full participation in society. 43% of respondents in the VFS who need personal assistance say that the number of hours of personal assistance is too low and is mainly sufficient for the most essential activities. Even for day-to-day activities, the necessary number of hours of assistance is often not allocated and persons with disabilities are forced to choose between different essential assistance needs. The number of assistance hours has decreased between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 2), although the need for personal assistance has not decreased. Decisions on assistance are often made on the assumption that family members will also provide support.

The legal minimum of 30 hours/month of personal assistance for leisure and hobbies has become a de facto maximum; excess hours require justifications to an unreasonable extent. Decisions below the minimum number of hours are also taken on the basis that the person is using housing services and allegedly receiving leisure assistance from the housing staff. However, as a rule, housing service contracts do not cover individual assistance for hobbies or maintaining social relationships. Many persons with disabilities do not receive any such assistance at all. Thus, what is described in paragraphs 217 and 218 of the Initial report is not translated into practice in the daily lives of persons with disabilities.

Application of Act on Public Procurement to disability services

The Act on Public Procurement and Concession Contracts (paragraph 214 of the initial report) applies to the provision of social and health services when the service provider decides to outsource the provision of services. In a tendering procedure, only the commissioner and the service provider are involved, leaving persons with disabilities behind with little involvement, influence and legal protection in matters concerning them. Competitive tendering has led, for example, to forced displacement or loss of education and employment (competitive tendering for interpretation services, Article 26). Competitive tendering has often had significant consequences for the ability and well-being of persons with disabilities: for example, the reduction in human resources in housing services through competitive tendering has reduced the quality of work and increased the use of restraint measures (Article 15). According to the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman, the way in which services for persons with disabilities with a life-limiting condition, such as housing, are procured should not be left to the discretion of municipalities and Kela[59] : “The often relatively short contract periods and changes of service provider involved in public procurement can bring considerable uncertainty to the life of a person who depends on individualized services every day.”

In 2018, disability organizations submitted a citizens’ initiative to Parliament to exempt services for persons with disabilities from the scope of the Public Procurement Act. Parliament rejected the request. However, an Inclusion Working Group was set up to prepare a proposal for legislation to strengthen customer participation in social care processes. This work, mainly carried out by OPDs, seems to have been largely in vain: the proposed legislation has been implemented to a limited extent only.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure the right of persons with disabilities to choose where they live, and with whom they live?

- ensure sufficient, competent, and permanent staff in residential services?

- overcome the institutionalization of residential care and the use of restraint measures due to the lack of residential care?

- ensure the application of personal assistance under the new Disability Services Act is in line with the Convention and the Committee’s recommendations to Finland and does not exclude people who act as employers with supported decision making from the service?

- ensure the number of hours of personal assistance is sufficient to meet the needs of the disabled person?

- ensure personal assistance is fully in line with Article 19 and the general comment?

- ensure the suitability of personal assistants for the sector?

- promote inclusive service provision for persons with disabilities?

- improve the ability of social services authorities to better identify and understand the impact of different disabilities and impairments on a person’s daily life?

- provide specialized training in social work for persons with disabilities equivalent to other areas of social work?

- ensure services for persons with disabilities are effective and based on individual needs?

- ensure coordination of disability services, multidisciplinary cooperation, and the necessary expertise?

- ensure adequate resourcing and staffing of services for persons with disabilities?

Article 20 Personal mobility

Inadequate mobility support jeopardizes the equal inclusion of persons with disabilities in all areas of life. The 2018 reform of taxi legislation significantly reduced the regional and temporal accessibility of transport services. The needs of persons with disabilities were not taken into account in the preparation of the reform. Of those in special categories who need accessible transport, 78% considered the change to be very or fairly bad, and 37% considered taxi access to be poor or very poor. The reform reduced equality[60], and some people lost the confidence to travel by taxi[61].

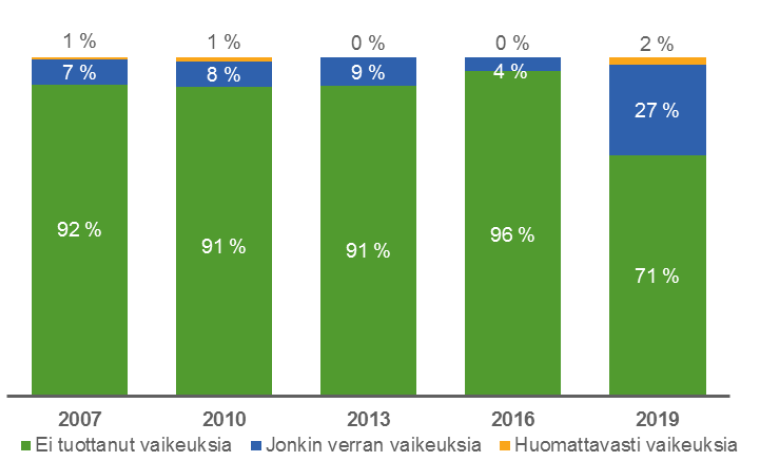

Transport services are the largest disability service in terms of number of users, with around 90 400 in 2019.[62] Transport service practices vary widely between municipalities and regions, and centralized transport referral systems do not take sufficiently into account individual needs. Inappropriate arrangements can prevent access to essential services altogether. Difficulties in the organization, quality and functioning of transport services have also increased since 2016, according to municipalities (Figure 3).[63] Services are unavailable, waiting times are long, and transport services do not meet the needs of customers. Legal changes were seen as adding to the difficulties.

The effects of the taxi reform are still being felt. In transport services, the professionalism and specialized skills of drivers have deteriorated, and tenders do not require any more the necessary professional skills. Service providers are not fulfilling their specific obligation to provide personalized transport services in line with customer needs. Procurement prices and contract terms do not sufficiently guarantee the right of clients to receive the service, and sanctions in procurement contracts for non-compliance by service providers are either inadequate or not used. Taxis increasingly fail to respond to orders they consider unprofitable.

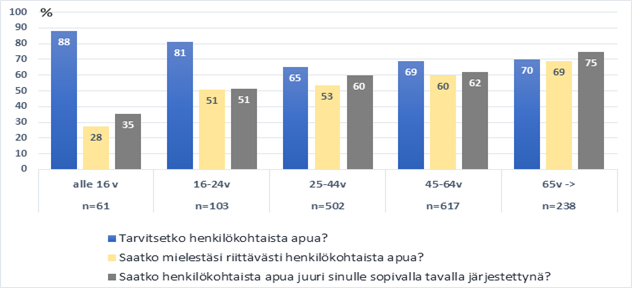

41% of respondents to the VFS felt that transport services are not organized in a way that suits them and that they do not receive enough service. For example, some must choose whether to use their limited trips to go shopping, to visit relatives or to take care of their children. Those under 16 and their families were less satisfied with transport services.

Also, according to the Advisory Board for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (VANE) survey[64] , 77% of respondents felt that the possibility of independent personal mobility for persons with disabilities is poor or rather poor.

According to the law, the amount of transport services must correspond to the individual need, but in practice individual discretion is not used and the minimum (18 one-way trips/month) has become the maximum. A disabled person can leave and return home 9 times a month with the help of transport services. The initial report (paragraph 246) does not sufficiently take into account the individual consideration of mobility needs, rather it refers to the average number of trips and misleadingly implies that on average trips are needed to an extent that is much below the minimum number. However, persons with disabilities are a heterogeneous group with varying life circumstances, and mobility needs, as they do for non-disabled persons. In a large, sparsely populated country, place of residence has a major impact: public transport is mainly available in large cities, and only partially accessible.

For a person with a disability who needs transport services, the functionality of transport services is an essential prerequisite for carrying out daily activities and living independently. Public authorities have a responsibility to provide transport services.

Proposed questions

What action will the Government be taking to:

- ensure the availability, reliability, safety, and driver skills of transport services?

- ensure that the legal minimum is not used as a maximum, and individual mobility needs are taken into account?

- ensure that transport services are guaranteed equally throughout the country, in both urban and rural areas?

- What will the Government do to ensure that the personal mobility schemes do provide financial support for the purchase of a car, including an electric car or other means of transport, for persons with disabilities?

Article 21 Freedom of expression and opinion and access to information

Linguistic rights are the basis for realizing the rights of persons with disabilities. The official languages of Finland are Finnish and Swedish (Initial report, paragraph 257). The Constitution also provides for linguistic and cultural rights for Sami, Roma, and sign language users, and for the rights of persons who need interpretation services because of disability to be protected by law.

According to the VFS, linguistic or communication rights are not practiced as required by law for persons with disabilities. In the administrative sectors of social services, health and police, linguistic rights are often poorly implemented and there are large geographical disparities.[65] Public authorities do not always serve customers in the language they use and documents, information or requests for opinions are not always translated into Swedish. There are also problems with digital services. According to the Chancellor of Justice’s Office, the Swedish language is disappearing from the administration and public authorities[66]. The situation has not improved despite legislative changes in recent years.

Two national sign languages are used in Finland, Finnish and Finnish-Swedish, the latter of which is classified by UNESCO as seriously endangered (less than 100 users). Despite government efforts to revitalize the language (initial report, paragraph 266), a deaf person who is deaf in Finnish-Swedish often ends up using Finnish sign language, has access to an interpreter who speaks only Finnish, and thus has to deal with matters in a language which is foreign to the person (Article 9). In 2020, the first Sign Language Barometer[67] showed the poor implementation of linguistic rights and interpretation services, to which the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman has also drawn attention[68].

Experiencing discrimination in access to information and communication is common. 67% of sign language speakers who responded to the VFS do not feel that information is accessible, almost 60% do not know how to react in case of danger and more than 50% had experienced inappropriate treatment in terms of language rights. It is difficult to read and understand official language. This is most difficult for old deaf people, who have less written language skills[69].

There are around 65 000 people in Finland[70] with a speech disability who cannot cope with everyday life using speech. For people with a speech disability, linguistic rights mean the right to express themselves in the most appropriate language or means of communication and to receive information in a form that is accessible and understandable to them (Article 2). Severe speech impairment affects a person’s overall ability to function, leaving a major role for those close to them to support and enable communication.

Public authorities are not sufficiently aware of their obligation to communicate in an understandable way with customers with speech impairments and service providers or authorities do not make the necessary reasonable adjustments, such as allowing sufficient time for consultation. According to the VFS, poor availability of assistants makes participation difficult. Many people would already need an assistant to arrange an interpreter or transport service. People often talk past a person with a speech disability to an interpreter or an assistant.

The right of children with speech impairments to express their views or receive information in a way that suits them is downplayed or ignored. Children who communicate by non-verbal communication are particularly vulnerable. Even at school, teachers do not always have adequate communication skills and children rarely have the support of an interpreter and a helper at the same time.

In the initial report (paragraphs 273-278), the most important service that promotes social equality and inclusion of people with hearing, hearing-visual and speech disabilities in practice, the Kela interpretation service, is described only in terms of its content and annual costs, not its practical implementation.